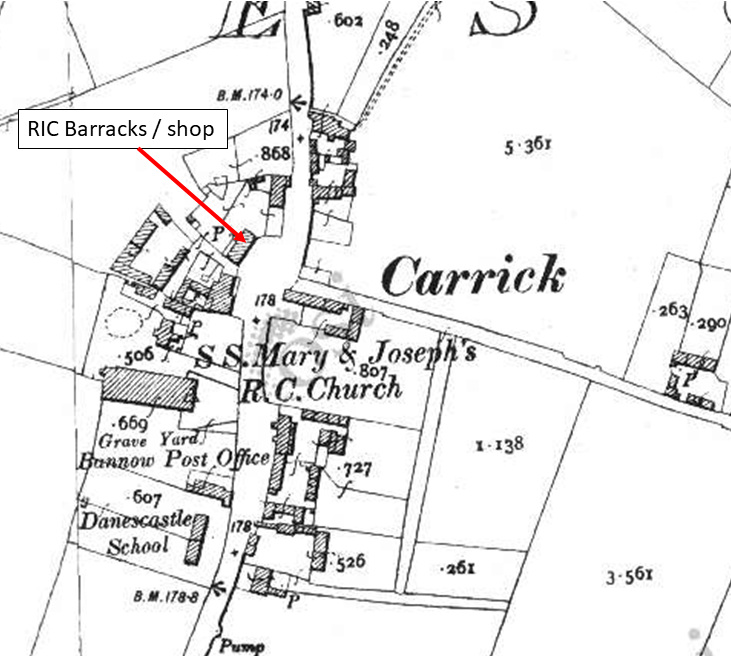

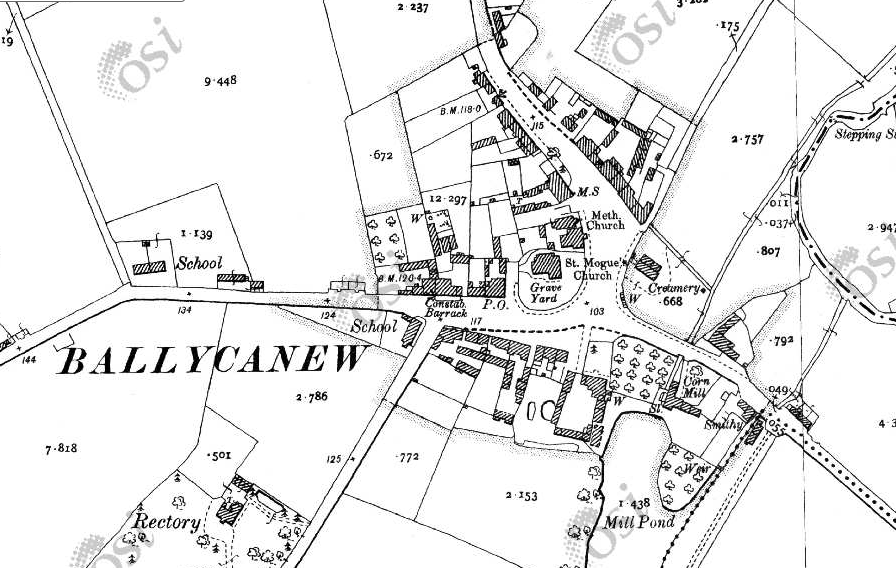

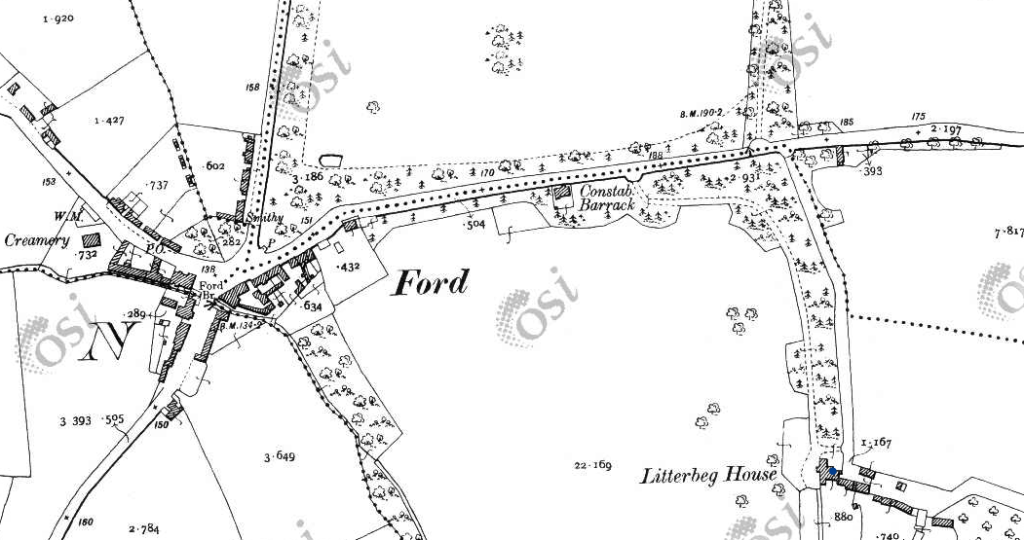

At about 2:45 A.M on Saturday the 18th of December 1920 members of the south Wexford brigade IRA launched an attack on the R.I.C Barracks in Foulksmills, a small rural village located about 22km west of Wexford town.

The Barracks

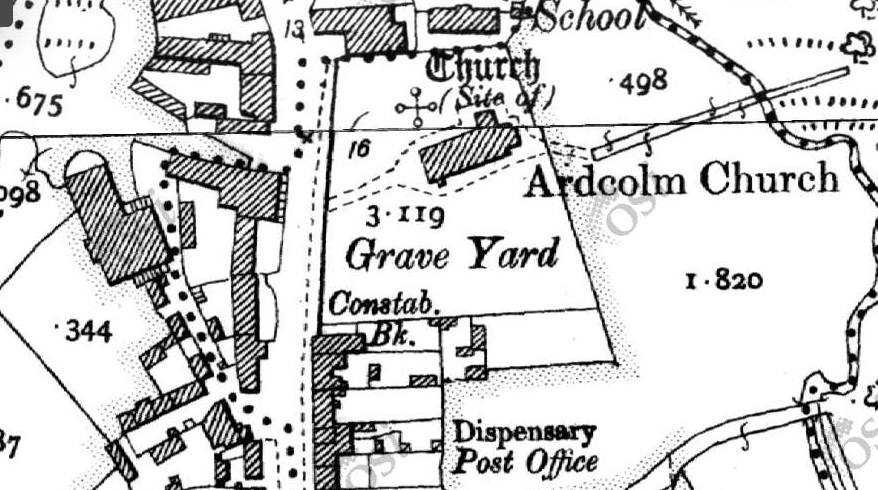

Before describing the attack it is good to get an understanding of the building which was the target. Thomas Howlett of Campile, a member of the south Wexford Brigade IRA, in his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History gave the following description of the barracks.

‘Foulksmills R.I.C. barrack was a solidly constructed detached building, with a slated roof. It was about eight or ten feet from the side of the road. Dividing it from the road was a low wall, surmounted by a railing. In the center and projecting from the front of the building was an entrance porch. There were two windows in front, on the ground floor. These, of course, had steel shutters with loopholes. The barrack was of rather unusual design, as there were no front windows on the first floor; there was one window in each gable end, on the first floor. In the ground floor gable ends were loopholes but no windows. At the rear was a lean-to, extending ten to twelve feet from the main building. As part of the defensive arrangements, barbed wire had been placed on all sides of the barrack, from the eaves to the ground, and extending about eight feet from the base of the building. (p5-6)

By December 1920 many rural barracks in Wexford had been vacated by the police and were subsequently either damaged or burned by the IRA so they could not be reoccupied. Additionally, there had been an attack in April on Clonroche Barracks. This increase in hostilities towards the police led to any remaining barracks becoming fortified, as Foulksmills had become, with the addition of barbed wire and steel shutters.

The New Ross Standard reported that on the night of the attack the barracks was occupied by 2 sergeants and 7 constables. It would normally have been occupied by 15 men but on the night of the attack some were on leave or elsewhere. The garrison may have included several black and tans.

The Attack

The attack itself was carefully planned; to isolate the barracks and delay the arrival of any unwanted reinforcements approach roads into the village were blocked with trees and the telegraph wires cut. Motor cars had be taken for the operation also to transport items and act as getaway vehicles. The New Ross Standard reported around 100 men were involved while the official military report estimated about 70. The IRA were armed with shotguns and revolvers but had no rifles at the time. The objective of the attack was to blow a hole in the roof using a mine. Once this was done grenades and bottles of petrol could be thrown through it into the building, while at the same time constant gunfire would be placed on the barracks. To get the mine onto the roof a rope was to be thrown over the building, one end of which would then be tied onto the explosive device. The other free end would then be pulled, levering the mine onto the roof, where it would then be detonated.

One man was to be given the task of throwing the rope over the barracks. This had to be done on the first go as they could not afford multiply attempts as it could alert the garrison inside the barracks. To ensure success the first time round the man given the task trained throwing a rope over a building in preparation. However, when it came to the night he failed to turn up and could not be located, despite a visit even to his homeplace. Instead, in a change of plan, the barbed wire surrounding the barracks was cut and the mine placed against the rear of the building. Once it exploded the firing began; men armed with shotguns that had taken up position behind a wall across from the barracks opened fire on the building and the police responded with their own. They threw grenades and sent up verey lights to illuminate the night darkness as well, in some attempt to help locate the attackers. Additional bombs were thrown onto the roof together with bottles of petrol. Fortunately for the garrison inside many of these failed to go off. With the failure of the bombs and supplies of ammunition beginning to run short the attack was called off just before 4 A.M.

House Commandeered

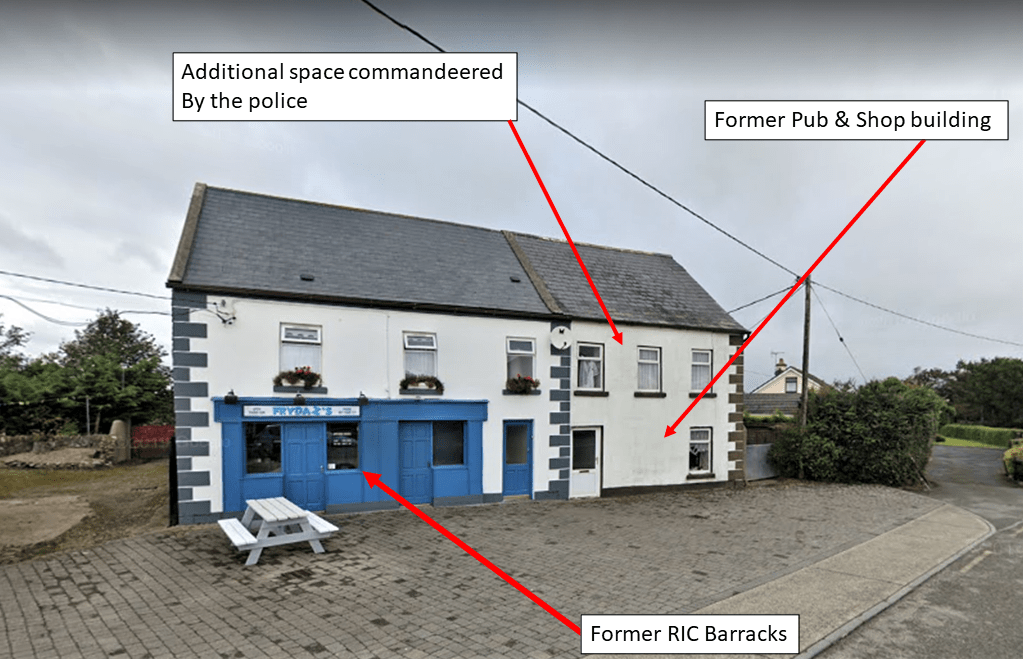

The New Ross Standard reported that prior to the attack 3 men knocked on the house of ‘Richard Doyle’, who lived 50 yards from the barracks on the opposite side of the road. The House was commandeered by the men and Mr. Doyle and his wife and family went to the house of a ‘Annie Jones’ where they stayed until the following morning. It was suggested they may have used the upstairs window of the house as a vantage point to fire on the barracks.

The home of a ‘Mr. Twomey’, directly beside the barracks, had an adjoining yard were the IRA also took up position during the attack. Mr. Twomey was in his house together with his wife and six kids on the night of the attack and they had to seek shelter together in a single room.

The Aftermath

No casualties were reported on either side and the following morning the police captured a quantity of bombs, arms and a motor car. Thomas Howlett in his witness statement told how after the attack himself and others returned to their motorcar only to find it hemmed in between two barricades and with the road blocking parties gone home. It then had to be abandoned. Interestingly the New Ross Standard reported that a Mr. Matthew Hart from Campile was arrested and brought by the military to Waterford after his car was found ‘…on the side of the road near Foluksmills on Saturday morning following the attack’. This was the same car that had to be abandoned as Thomas mentioned how prior to the attack they commandeered Hart’s car to transport bombs and bottles of petrol.

The failure to capture the barracks is due to several factors. Firstly the individual trained to throw the rope over the building failed to show up which meant an abrupt change of plan was required. Secondly, many of the bombs used failed to go off and breach the roof. Thirdly and last is the lack of experience as pointed out by Thomas as he said ‘I believe that if we had even one man with experience in barrack attacks we could have captured the barracks that night.’ (p7).

Later Attacks

The Barrack was attacked again in March 1921 while a month later on the 13th of April an RIC constable on the road in front of the barracks was fired upon from behind gorse bushes 600 yards away. Fortunately his attackers missed and the bullets embedded themselves into the barracks walls instead.

Martin Walsh in his witness statement to the Bureau of Military History recalled another attack in May of 1921. Its purpose was to force the police to send up Verey light that would alert reinforcements which in turn would be ambushed by a newly formed battalion A.S.U. A landmine was placed against the barrack wall which exploded and was followed by shotgun fire on the fortified building. The police responded with their own fire and flung hand grenades outside. Unfortunately for the A.S.U the reinforcements arrived and left via a different route than the one set for the ambush and therefore they missed their opportunity.

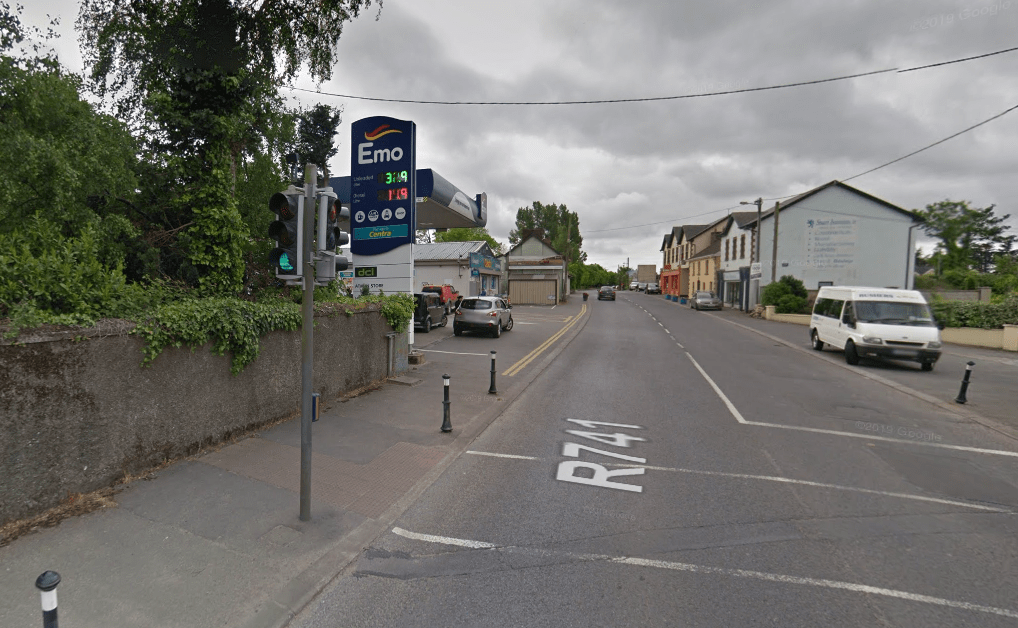

The Site today.

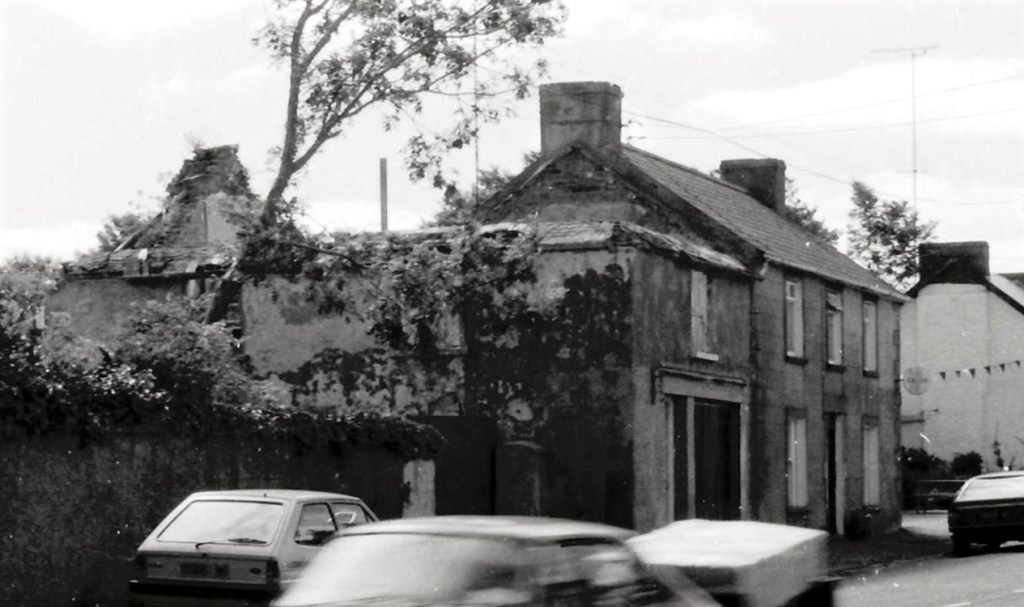

Many of the physical elements associated with that nights attack no longer exist ; the Doyle and Twomey houses no longer remain, neither those the concrete wall which the men hide behind. However the barracks, which is now a private residence, still survives. It remains much the same as it would have looked in 1920. The building retains its gable end loopholes from the period. Bullet holes are also visible on the front wall associated with that nights attack in December 1920.

Sources

Bureau of Military History Witness Statement: Martin Walsh (IRA) #1495

Bureau of Military History Witness Statement: Thomas Howlett (IRA) #1429

New Ross Standard, Friday 24th December 1920, p4

Belfast Newsletter, April 15th 1921, p3

South Wexford Brigade Activity Reports